How piracy made game culture thrive in my small Indian town

What happens when all you can get is a handful of pirated games? And what changes when you can finally buy everything ever made?

“Whoa, who’s that?”

“Dante. He slaughters demons and eats pizza.”

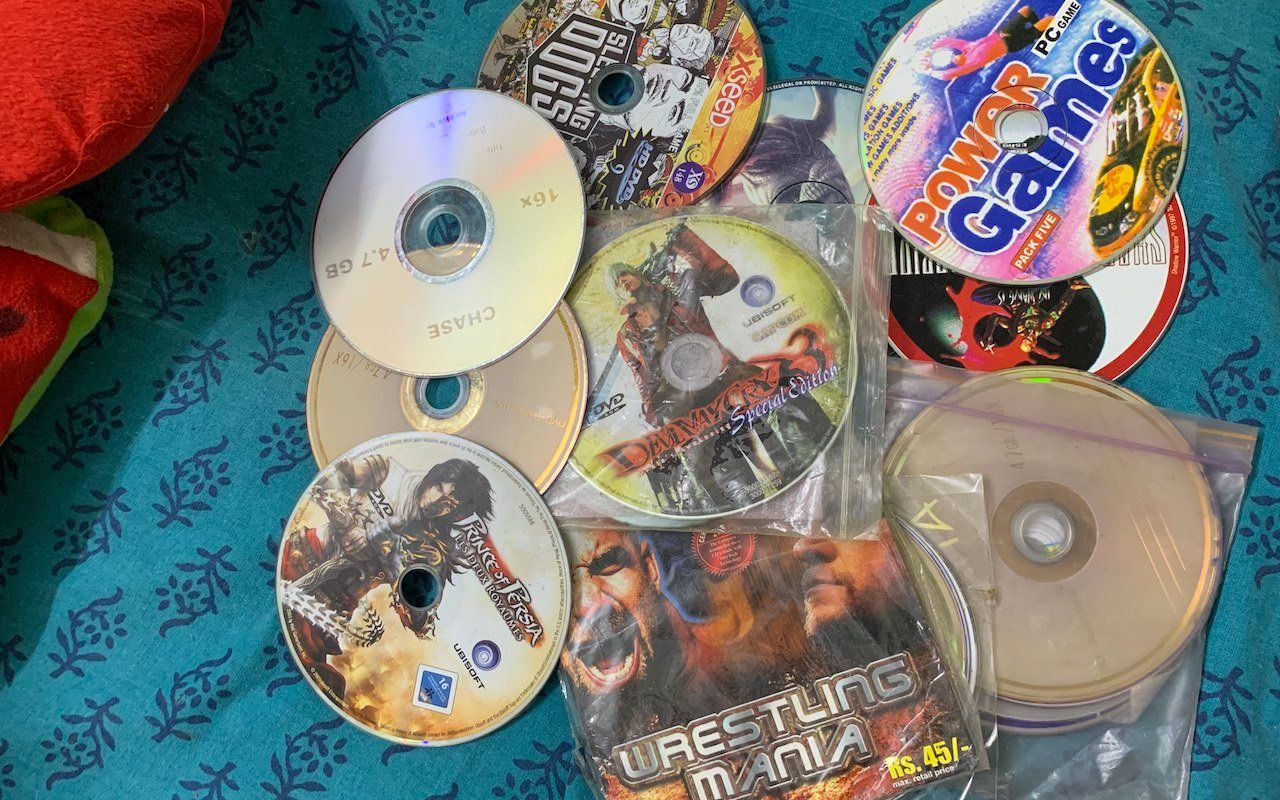

In a small Indian town, hundreds of miles from the one I call home, tucked inside a dingy internet café, joystick in hand – I had an awakening. One week later, I returned home with a pirated copy in tow, and introduced my comrades to the gore and glory of Capcom’s exhilarating, maddening action-adventure – Devil May Cry 3: Dante’s Awakening.

Huddled in front of one of the two computers the town shared, we witnessed a revolution. Our horizons expanded in front of us, stretching far beyond the bounds of our hamlet of a town, to include a world not limited by the whims of one storekeeper and his uninspired collection of bootlegged games.

But I am getting ahead of myself.

Welcome to Dhupguri

Our story begins in tiny, unassuming Dhupguri. Tucked into the foothills of the Himalayas, Dhupguri was a few decades late to every party, every trend. So, in the late ‘90s and ‘00s, as the world toppled headfirst into the online era, Dhupguri unsurprisingly missed the notice.

In my childhood, access to any media was fickle and usually stolen. There were no bookstores. The cable guys created an odd system with hooks and wires to pirate channels. Cartoon Network – if available at all – was often in another Indian language we didn’t understand.

So this is where we set our scene – in a town where we read about cheese and pastries in Enid Blyton books and the words PlayStation and Nintendo were fascinating gibberish.

Little but loved

Sometime in the late '00s, I became the proud owner of a Windows XP device. The only other computer in town was owned by a school junior and a fellow would-be gamer.

It was the epitome of privilege. We were kings. We could play Roadrash – this crazy, wonky game with the worst possible visuals and soundtrack. And it was the one game available at the only store that sold computers in our town for a bit before going swiftly out of business.

My friends and I didn’t mind, though. No, in fact, we spent the next few months playing every possible track till we collected all the bikes, stars, and booty. Then defeated opponents while perched atop wobbly old rat bikes, feeling like princes of vagrants after each win.

And vagrants we were. We just didn’t know it yet. Because things had improved dramatically for the more accessible small towns by 2006. Our friends were playing Counter-Strike and Vice City and following the evolution of GTA at a time when I first got my hands on a device that I, for the longest time, thought was a Nintendo.

The console came with its own terribly loud keyboard, a plastic gun, two joysticks, and bootlegged cartridges that promised “99 games in 1!” but almost solely offered many, wonderfully different versions of Super Mario. But this buggy old console that burnt a spot on my mum’s favourite table that time one side of the keyboard melted was also the one that introduced me to the tale of Link and Zelda. One cartridge - always in need of constant tinkering and granting me a well-earned electric shock or two - was also the one that let me spend hours as Spiderman, swinging gaily from buildings, punching villains and delivering pizzas while at it.

Access, awe, adamance

The revolution arrived in Dhupguri towards the tail-end of the ’00s. It was in the form of two stores - one that sold pirated CDs and an internet cafe that boasted a humongous box with a glitchy screen and two in-built joysticks – the small-town version of an arcade cabinet. It had just the one game: Tekken 3. And that’s how my hometown began catching up to the madness that had already begun taking over other small-but-less-forgotten towns.

Every child and teen started spending every conceivable minute and money just to get a turn on this wondrous machine. My friends and I, children of stricter parents, were not allowed to partake of its delights much, however. So the pirated CD store – like for so many others our age, stuck in similar backwater towns – felt like our lord and saviour.

The store boasted four or five different game discs at a time – the rest of the space taken up by steamier forms of media. Limited as our resources were, we would pool all our money together and buy these games one at a time. We would each then take turns on a game until it was so scratched that even thorough cleaning and careful polishing with layers of vaseline could not salvage the remains.

Then it was time to buy the next game.

For years, this system sustained our habits. Sometimes, one of us would go to the nearest “big town” and get access to an original game CD. These moments were precious few and cause for celebration. But honestly? We didn’t know the difference. Perhaps the visuals were better. Perhaps the original discs lasted longer. But our computers were old and battered and treated every game with the same disdain.

I still remember the time my friend, Ronit, in his haste to get the game to me, tucked the Max Payne disc into a notebook and threw it towards me from a running bus. The notebook and the game were, sadly, never found again. And while I remember the earful I got from him in class the next day, I don’t remember if that was an original disc. That didn’t matter. It was a loss all the same. I didn’t encounter the game again until years later when I moved to a metropolitan city for my studies.

But, by then, things had changed.

An alarming abundance

In the ‘90s and ‘00s, in small Indian towns like Dhupguri, the story was largely the same. Lack of internet and gaming stores, coupled with limited finances meant lack of access. But, as I swapped stories of such days with Pratik, one of the OG members of the club, he mentioned how that also kept us hooked.

We didn’t care what the game was. We couldn’t afford to. Whatever we could get our hands on became priceless – Roadrash, the pirated versions of Codename 47, and Marine Sharpshooter inspired the same delight.

We played Obscure even when the nightmares kept us up at night. And cheered the first time we watched Dante swish his signature dark red coat on screen. Our taste in games, and gamer personalities, were defined as much by access – or the lack thereof – as by this odd camaraderie.

So, it is perhaps not surprising that when I moved to the city for college, armed with a hardy laptop and enough pocket money to buy a game or two, the excitement and the intrigue slowly fizzled out.

Should I blame it on the sudden access to fast internet and the big game stores in shopping malls? I could not keep up – not with the million devices and various versions of each game, not with the community that questioned your gamer status if you didn’t have access to those devices or hadn’t grown up playing particular games.

The access, and what you had to do to keep up with it, scared me away. And even that was a few years ago.

We lived a simple, sheltered life. The realisation is now bittersweet. Pirated discs gave us dimensions and universes that we could not hope to access otherwise. That meant fewer, glitchier games, but it also made us intrepid explorers – ready to partake of any delight this weird, wonderful world had to offer.

Gaming and us, we were star-crossed lovers – the impossibility of our situation burning our passions brighter. Maybe that’s why I still have a gaming laptop, but haven’t played games in years. And why I keep a long-battered copy of DMC3 around – ready for the day I cave and let the haunting notes of the prologue summon me back home.

Byteside Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.