A retelling of anxiety through the thoughtful platformer Celeste

Unlike so many media depictions of anxiety, Celeste reflects the messy, non-linear nature of dealing with mental illness.

I played Celeste in April, three years after its release. As a platforming enthusiast, this should be surprising. The game received unanimous praise for its level design, platforming mechanics and emotional story.

Putting aside my slow recognition and subsequent decision to move Celeste from Wishlist to Steam Library, the move was ultimately well timed because my recent relapse into generalised anxiety disorder elevated my connection to the narrative.

The messiness, confusion and sabotage that consumes us through anxiety is entangled in our protagonist Madeline. While on a quest to climb Celeste Mountain, she must face the manifestation of her mental illness to succeed. As a result, Celeste painted my life living with anxiety through its story over just a couple of days.

At 12 I was diagnosed with anxiety after experiencing what appeared to be unrelated symptoms. I developed insomnia from a self-perpetuating cycle of fear that I would be unable to sleep. This in turn stopped me from sleeping. I was simultaneously suffering from gut pain that, after landing me in hospital a few times, doctors could find no physical diagnosis for. I was unable to recognise my pain and fear as part of a larger pattern because, as a child, I lacked self-awareness. Instead, I unconsciously engaged in behaviours akin to Madeline in the first chapter of her journey.

"This is it, Madeline. Just breathe. Why are you so nervous?"The game's opening line.

Madeline is introduced, first and foremost, as anxious and suffering from self-doubt. And secondly, as a character that is defensive and stubborn.

Upon starting her journey Madeline meets Granny, an old woman who lives on Celeste Mountain and knows of all its secrets. However, when Granny warns Madeline of the challenging plight ahead of her, she is quick to reply with a scathing remark and a quick deflection.

The opening line informs us of Madeline’s anxious undertone, which in turn explains why she has this reaction to Granny.

Very early into dealing with my own anxiety, deflection, anger and defensiveness were common reactions to even the slightest attempt by others to guide my actions. Madeline engages in this same push back to unconsciously protect her own self-worth and as a consequence repeatedly appears stand-offish to the characters around her. Years of self-doubt began to manifest as the first signs of unmanaged anxiety just as I struggled with as a child.

After my diagnosis, I started seeing a child psychologist to manage my symptoms. It wasn’t as clinical and dreary as my terminology might suggest. Most days it didn’t feel like I was in a clinic at all.

Each session my psychologist would carry in a box of arts and crafts, games and fidget toys that would live in my room for years after seeing her. I had a wall filled with drawings of my happiest memories, trees with branches made from calming words and feelings and comics of my feelings personified into characters.

I remember we would begin our sessions with me lying on the couch. My psychologist would tell me to close my eyes and imagine I was floating down a river. The water was lapping at my sides, drifting me downstream. The sun was a warm touch to my cheeks and birds chirped around me.

I breathed in and out.

"Picture a feather floating in front of you."

Reminiscent is this line from Celeste, where Theo, a fellow climber wishing to test his mettle, teaches Madeline a technique to regulate her anxiety while they’re trapped inside a malfunctioning gondola.

A feather appears on the screen as Theo takes Madeline through the breathing exercise. Madeline breathes in, you control the pace of the feather ascending. She breathes out, the feather floats down the screen.

You repeat this mechanic until the music starts to slow, the gondola stops swaying and Madeline’s anxiety attack passes. I felt elation for Madeline as she controlled her anxiety for the first time instead of engaging in unhealthy behaviours. For myself, this technique was the turning point for my early age anxiety.

Time passed and my symptoms faded with the aid of my learnt techniques, but anxiety is a tricky mental illness that never quite leaves once its been triggered. It can lay dormant for years and reappear in a different form.

In my case, it crawled back into my life in a way that went unnoticed for most of my adolescence. People pleasing with a side of saviour complex often gets confused as an admirable trait, because it possesses positive characteristics like care, agreeability, selflessness and kindness, but it gets taken a step further when everyone else’s needs are more important than your own.

During Madeline’s journey she reaches the run-down and abandoned Celestial Resort Hotel, empty except for its owner, Mr. Oshiro, a disillusioned ghost unable to accept his resort has shut down.

As Madeline ventures deeper into the resort, finding it has manifested into Mr. Oshiro’s twisted mind palace, she increasingly ignores warning signs of his dangerous tendencies and instead bolsters her resolve to save him.

I toed this line many times in my adolescence, because saving people made me feel good about myself. Imagine my self-worth was a well, and no matter how many good deeds or kind gestures I did it was impossible to fill. The brief elation I felt saving people was quick lived, because the problem lied in my belief that I had to save people in order to be loved.

Madeline admits to Theo, when he asks why she is helping Mr. Oshiro, that "maybe I can actually do something good. For once."

Unfortunately, Mr. Oshiro wasn’t ready to face his own fears, nor was he after help, so he chased Madeline out of the resort after it almost collapsed on the both of them.

Dejected, Madeline learnt a hard lesson that saving people will never fix her own self-worth. Learning to separate my own self-worth from my actions was a difficult process, because I was forced to confront my own beliefs about myself, which didn’t happen until my anxiety reached a breaking point last year.

My relapse was intense and overwhelming, unlike my previous experiences that began as unconscious behaviours; I developed paranoid and catastrophic thinking to benign circumstances that felt impossible to rationalise myself out of. They would sit in the back of my mind and grow until they were screaming for my attention. I would dread the moment my anxious thoughts were triggered, because there was no way to escape them, and eventually they followed me around from morning to night.

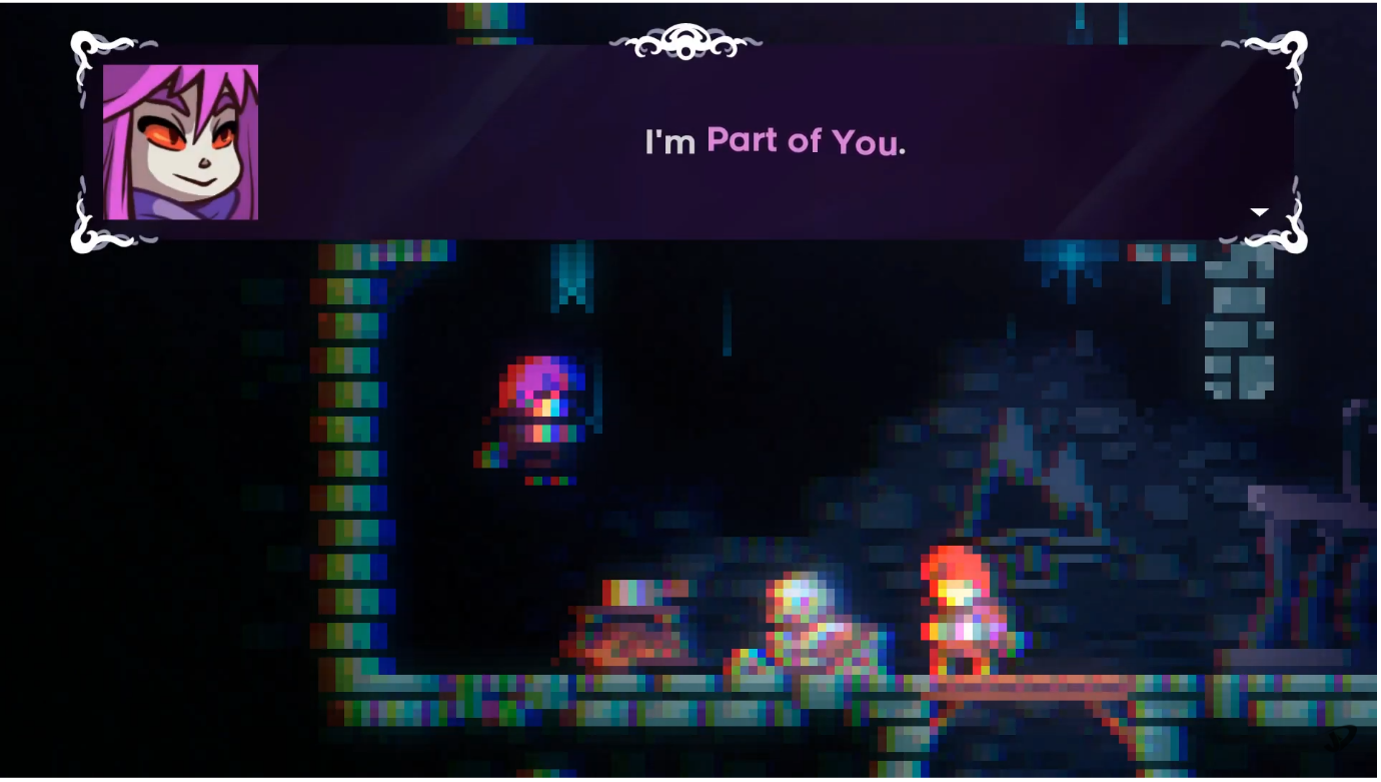

These thoughts felt like a separate entity had made a home in my head identical to the psychical manifestation of Madeline’s worst fears and anxiety: Badeline.

Badeline is Celeste’s main antagonist. She appears multiple times during the game to sabotage Madeline’s attempts at climbing Celeste Mountain with cruel words, manipulation and aggression. She is rumoured to have been created by the magical properties within the Mountain in order for Madeline to face her problems head-on. Granny mentions "the Mountain can’t bring out anything that isn’t already in you", which suggests, and is later confirmed, that Badeline is the manifestation of all of Madeline’s insecurities.

When Madeline steps forward, Badeline is there to pull her back. The narrative progresses as a tug of war between Badeline’s best attempts to poison Madeline’s confidence and Madeline wrangling with Badeline's beliefs.

Often, Madeline is overwhelmed and overpowered by her counterpart and asks, "Why are you so cruel?", which Badeline replies "Because you deserve this".

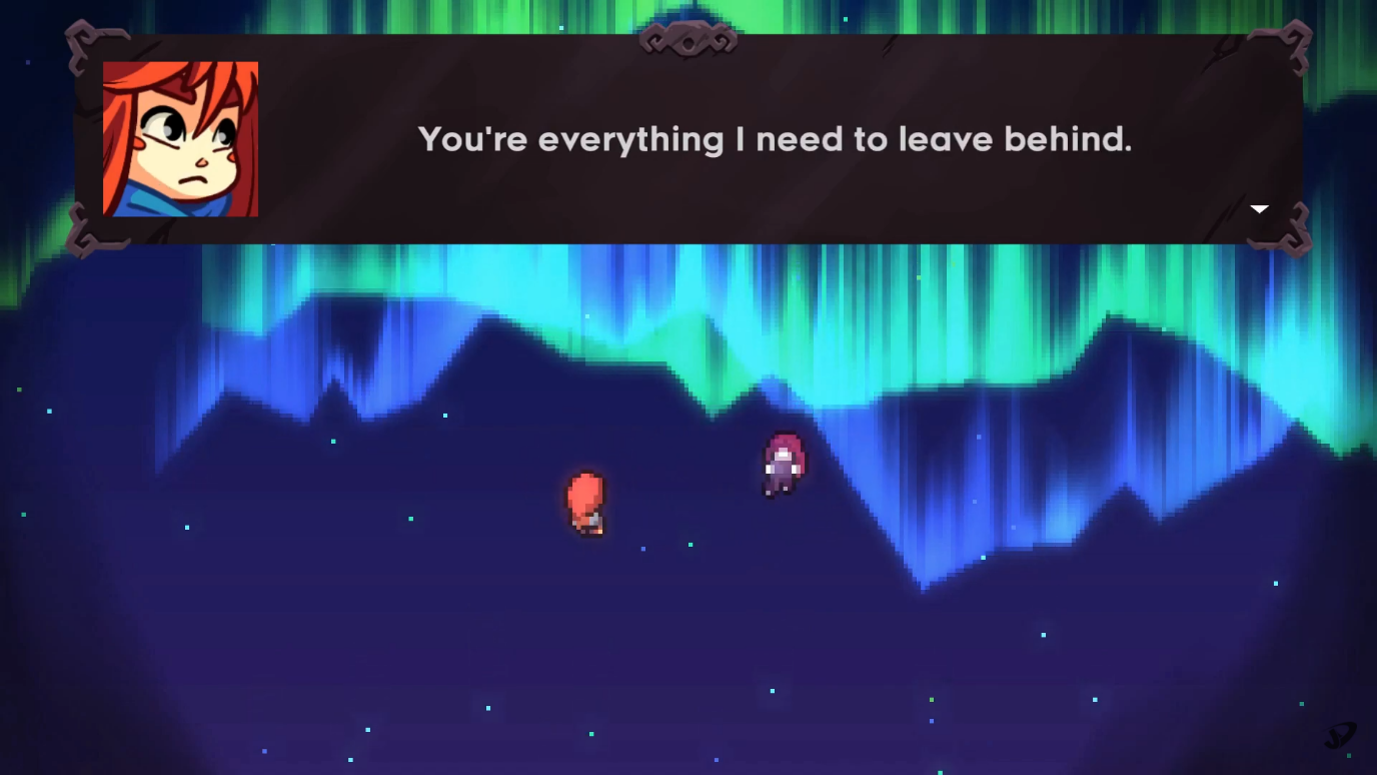

Despite Madeline’s inability to persuade or control Badeline’s impulses, she begins to gain confidence throughout her journey and comes to believe that she doesn’t need Badeline anymore:

"I am setting you free. We’ll both be so much happier."

Although these lines are heartfelt and intentional, they allude to the wrong solution to Madeline’s problem.

During the throws of my worst anxiety, I found it easy to blame my problems on my mental illness and subsequently, rejected its presence in my life. At every turn, I fought against it, and I remember feeling disappointed with Madeline’s solution, because in my experience you can’t make anxiety go away.

To my surprise, Badeline bites back.

"You think you can just leave me behind?"

What transpires is the worst manifestation of Badeline’s anger: physically throwing Madeline back down Celeste Mountain.

That scene validated my struggle tempering anxiety. All too often media presents a perfectly wrapped solution to mental illness. Problems will disappear at the first instance of mitigating conflict and characters, seemingly out of nowhere, overcome their difficulties to become different people.

Instead, Celeste respects the journey of those of us mentally ill and highlights our non-linear struggle.

The sixth chapter of Celeste is named ‘Reflection’. As Madeline climbs her way out of the crystal cavern Badeline threw her into, she starts to understand that Badeline’s behaviour was simply because she was scared.

The realisation is almost anti-climactic, but it certainly was the reality behind my worst and intrusive symptoms. A fear of rejection, fear of failure, fear of suffering, all twisted into a defence mechanism that did more harm than good.

When Madeline finally confronts Badeline, it is with an open heart and unrelenting perseverance that chips away at her defences until it all crumbles down and her small fearful self is revealed.

Celeste held a mirror up to my behaviours, coping mechanisms and defences and laid them all bare in front of me.

I learnt, alongside Madeline, that it isn’t until I hold my fear close, soothing its thrashing feeling, that the separate entity I call anxiety can feel safe enough to settle.

And that I can reach the Summit, together with all my fears and pain, just as Madeline did.

Byteside Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.