Paradise Killer and Vaporwave: more than just an aesthetic

Talking to Oli Clarke Smith, Creative Director of Paradise Killer, we look at how the vaporwave genre and aesthetic have evolved.

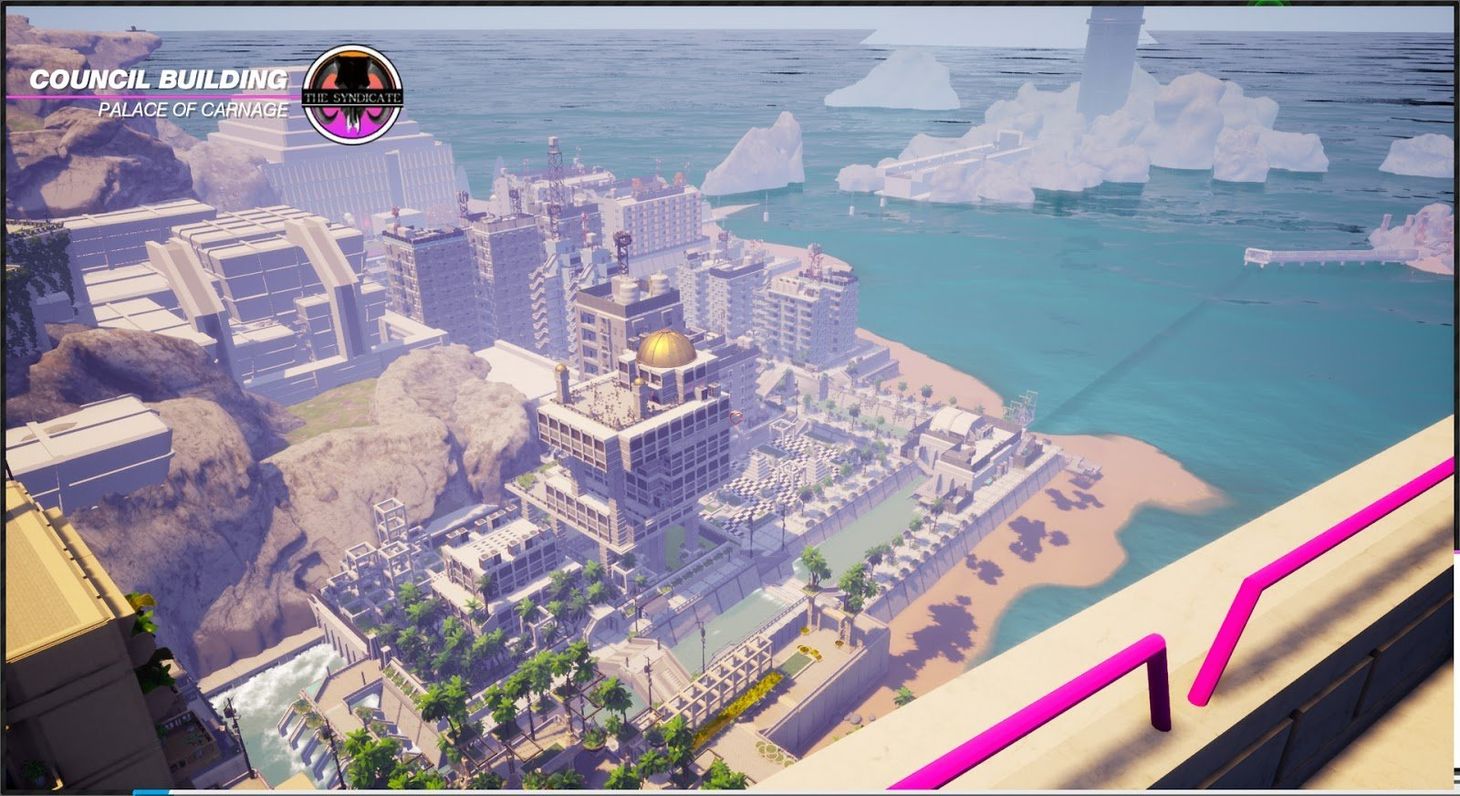

A lonely island, devoid of life but filled with remnans of human citizens. Bizarre vaporwave architecture creating a dreamlike world, a cast of characters enveloped in a power vacuum caused by a murder mystery.

At the centre of it all is Lady Love Dies, the hero of 2020's Paradise Killer, determined to unlock the mysteries layered in plots upon plots upon funky tunes. It’s a carefully thought out entire product that takes vaporwave further than just a meme aesthetic of recent years, and thrives on using it as a commentary, a setting and a culture for the world of the game.

I spoke to Oli Clarke Smith, Creative Director at Kaizen Gameworks, the studio behind Paradise Killer, about how the strange internet subculture wound up in their game.

What exactly is vaporwave?

Vaporwave is a genre of music that began popping up in the early 2010s as a bit of a gag. The idea was taking internet culture, Japanese culture, 80s/90s jazz and elevator music, a healthy dose of nostalgia and then mashed all together because it was pretty funny. But then it really caught on and became something much larger than a meme, producing its own subculture.

Vaporwave continued to evolve and has developed a wealth of its own iconic imagery, from Roman busts to old technology, usually overlaid on some kind of island or secluded landscape.

It also began to explore recurring themes of a technology obsessed culture, rampant consumerism and an ironic sense of 'death comes for us all, let’s chill out about it'. There’s elements of copyright culture in the sampling of the music, taking from fast food advertisements through to elevator jazz, and a key part to how artists can construct their own commentaries.

When asking Clarke Smith how he came to discover vaporwave, he explained he started in a punk band with fellow Kaizen Gameworks creator Phil Crabtree, though found the scene had begun to die down.

"Not enough new blood was coming into it. There are amazing new UK punk bands emerging all the time but the scene was losing its momentum," Clarke Smith says. "Vaporwave has the same DIY feeling as punk but its themes are much more contemporary and it can do things punk never could at the time. The internet allows vaporwave to flourish in a way that punk couldn't in the early 2000s."

When pressed to recall a specific moment when he found vaporwave, he points to encounters with the YouTube algorithm.

"I think I discovered vaporwave via YouTube recommendations after enjoying lots of illegally uploaded PS1 soundtracks on Youtube," he says. "Some of them are very vaporwave – especially Divers Dream, for example – and that console has been hugely influential on some vaporwave artists."

Vaporwave in Paradise Killer

"We didn't set out to make a vaporwave game or exploit the aesthetic, it was something that grew organically," Clarke Smith explains. "The way we develop is to start with a small idea, start implementing it and let the game reveal itself to us. Our content pipeline is very rapid and our team size is small and agile so we can respond to what we think the game needs as we discover it."

"The vaporwave themes grew as the writing and environmental storytelling developed. We realised that we were making a very left-leaning and critical game which in turn caused more vaporwave aesthetics to creep in to the 2D art."

The game takes place on a large island ruled by the Syndicate. A group of immortals worshipping their dead alien Gods, who have gifted them the power to create these strange islands outside the realm of space and time. As such, everything from the natural landscape to the architecture is rife with surreal imagery spliced together with the mundanity of apartment blocks and vending machines.

With each island, the Syndicate brings in humans from our world to serve as, essentially, cattle. They maintain the island, their blood serves as literal currency (for example, vending machines take 'blood crystals') and at the end, when the new island has been created, only the Syndicate moves on while every citizen on the island takes part in a ritualistic mass sacrifice.

The Syndicate and the murdered Council, the group the games mystery surrounds, is teeming with corruption and hypocrisy. The worship of dead alien Gods and the squabbles of humans-turned-immortals are just as messy as any other society we’d see on Earth. In-fighting, petty bickering, elevating themselves to the status of celebrity rather than any kind of leadership.

It’s a grim reality for the citizens, and even Clarke Smith himself isn’t entirely sure to what extent that reaches.

"The Citizens are forced to worship like slaves, so their devotion is forced rather than voluntary. I don't know if they'd ever be made aware that a ritual sacrifice awaits them or not," he ponders. "I was never sure about that… They definitely know how fucked up this world is but there's nothing they can do. They are forced into a daily schedule of worship, working in the factory and worship."

He continues to explain, detailing the parallels between overt slavery and other forms of servitude that seep into our culture in ways we often fail to notice.

"Obviously the modern world has a very explicit slavery problem but it can also be more insidious. We are all under the yoke of debt and capitalism. The elite try to create an illusion that this is what happiness is but the horrors of modern society are plain to see all around us."

The themes and parallels to the real world are also seen on a smaller scale in characters like Carmelina, the architect responsible for creating the islands.

"...One of my favourite pieces of hypocrisy is Carmelina's evangelising of displaying function as form in her architecture," Clarke Smith says. "I am a big believer of not hiding away from the function of things. Carmelina says she also believes in that but the functional parts of the island are hidden from view to the Syndicate. You can't see the farm or the Deep Factory. Most of the Citizen housing is obscured from view. Anything that the lower class does that allows Carmelina to live her life of privilege isn't in her view. This isn't a crucial part of the game but without realising it we incorporated social critiques into the environment art, dialogue and 2D art."

Even some of the more subtle features, such as the car belonging to Lydia the ferrywoman being named ‘Burn Parliament’, come back around to the lived experiences of Clarke Smith and Crabtree.

"They'd always be filtered through our own perspectives and the perspective of the game… The Gods are a ruling class of capricious idiots that only focus on personal gain and their whims, just like our ruling class in Britain."

The game is not all negative takes, with the aesthetic being a very light-coloured one. And despite the hidden darkness, there are themes of acceptance and a world where everyone is free to be themselves, with a celebration of the individual – whether you’re a red skeleton man or an obnoxious personal assistant.

But Clarke Smith points out this is also a luxury only for the ruling class. Which the player character was, and potentially still is, a part of.

"We purposefully made sure that you were on the side of this universe's ‘bad guys’ and wanted to let you have the option to question it, show your disdain or just go along with it. Shinji makes our intentions very clear in a couple of bits of dialogue but otherwise the player is allowed to determine their own feelings."

Paradise Killer is, in essence, able to be summed up by a Suda 51 quote from a Eurogamer interview Clarke Smith alluded to when I spoke to him:

"In No More Heroes you sit on the toilet to save the game – I guess making a game for me is a bit like that. When you take a shit, everything you’ve consumed is all mixed together, there are all sorts of things in that – and that’s the same kind of idea, I think."

What we create, and even vaporwave as a genre, is a mixture of all kinds of influences both personal and external, and how we interpret them to create a finished product. And, just like the quote, it doesn’t really have to be a sophisticated thing.

It can be crass, it can be funny, and it can still be meaningful.

For Clarke Smith personally, this was taking things like "'90s game aesthetics, JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure, being angry at the world, DIY punk, the terror of eldritch beings from space and Japanese architecture."

The result is a dreamlike world that, despite its surreal nature, is still anchored firmly in ideas and themes from our own world, and the idea that even in a 'paradise', it’s still going to be familiar in the most uncomfortable of ways.

But the good part? It looks and sounds absolutely spectacular.

Byteside Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.